Many current downtown dwellers have lived at least a season

or two in Riley Towers Indianapolis ,

opportunity for real, big-city living. Few of us realized we were in buildings

that are historically significant.

Riley Towers is now past 50 years old, the minimum age at

which the project could become eligible for listing on the National Register of

Historic Places. Its contribution to the city and state’s sparse collection of

significant modern architecture could earn them a place.

The towers are not architectural marvels. They’re not an

exclamation. But they are a modern architecture statement in a city that can’t

claim many others. And they are, to this day, the state’s tallest residential

structures.

They are perhaps even more significant for their association

with the urban renewal plans of Indianapolis

business movers and shakers of the 1960s and this city’s unique approach to

funding those plans. Ironically, they are also significant for their failure to

change Indianapolis

residents’ vision of what it meant to live in the “City of Homes .”

Construction began on the buildings of the Riley Center City-County Building Indianapolis . If, as Mies said, “God is in

the details,” then Riley

Center Riley Center

Architect Vickrey designed the towers of reinforced concrete

construction with curtain walls that hung upon the framework but bore none of

the building’s weight. According to the Indianapolis News, Vickrey used a construction technique that was new in

the United States

at the time: first building a central concrete utility core and then mounting a

crane on top of it to lift materials into place as workers built the exterior higher

and higher. (A practice that is now common in new construction). Inside the

utility core were stairwells, elevators, and heating and air conditioning

“chases” for piping and ductwork.

The Riley

Center Twin Tower

Between the south Crown

Tower Twin Tower

During construction, local newspapers noted that Riley

Center’s architect stressed the “human

element” in the buildings’ design and function and made a point of avoiding

“regimentation and institutional appearances” in his work.

According to the Balconies provided “unparalleled opportunity for apartment

dwellers to enjoy outdoor living.” Their unsupported cantilevers mounted on the

building’s glass curtain walls also made a clear, modern statement that was, to

say the least, uncommon in 1960s Indianapolis .

The business elites involved in funding Riley Center Indianapolis

“who’s who.” The Indianapolis Star reported that, along with Frank E.

McKinney, chairman of American Fletcher National Bank (which opened a

branch on the first floor of the south tower), sponsors also included Thomas W. Moses, at that time president

of Investors Diversified Services (later chairman of the Indianapolis Water

Company), G. William Raffensperger,

president of the investment firm, Raffensperger, Hughes and Co., C. Harvey Bradley, chairman of the

executive committee of P. R. Mallory and Co., and Harry T. Ice, partner of the law firm of Ross, McCord, Ice and

Miller (now Ice Miller), among others.

Not since the construction of Lockefield Gardens in the 1930s had Indianapolis seen such an ambitious

residential building project. And like the Lockefield Gardens Riley

Center

The developers proudly used local monies rather than federal

urban redevelopment funds for Riley

Center Indianapolis ’s urban

renewal plan apart from those elsewhere in the U.S. But, even though the architect

and project director claimed in an Indianapolis

News article that local funding “expedited the project by at least five

years,” it probably also eventually caused it to fall far short of its

potential.

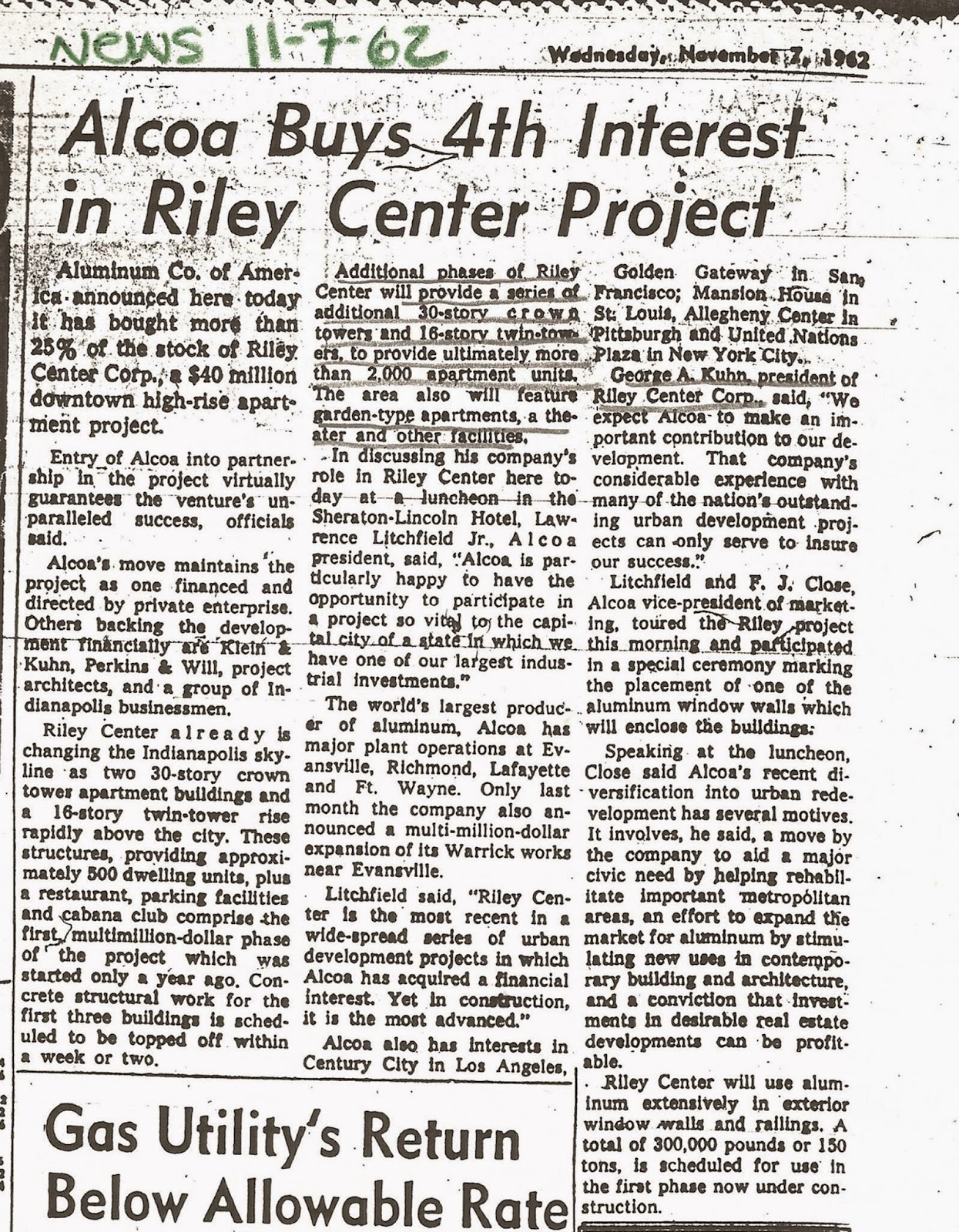

To fund their initial four-building phase in the project

they hoped would eventually see as many as ten of the 30-story “crown towers” and

several 16-story “twin towers,” the businessmen sponsors got a $9 million

mortgage and sold 25 percent of their Riley Center stock to the Alcoa Company to help raise the rest of

the $40 million required. In return, the architect used Alcoa aluminum extensively

in the exterior window walls, entry doors, and stair railings.

On the inside, according to the development's promotional materials, the Riley Center

Only “reputable and responsible citizens” would reside in

the apartments.

The Riley

Center Meridian Street ).

Even with all these attractive (not counting the Muzak)

amenities, the project developers knew they had to be creative to sell the idea

of renting apartments to Indianapolis residents, who were among the most likely

in the nation to embrace home ownership.

A 12-page insert in the May 19, 1963 , Indianapolis Star painted Riley Center

Despite those inspiring words, the Riley Center

Although the Riley

Center

Sadly, the project’s lack of immediate success continues to

limit the skyline of Indianapolis

to this day. Worries about high-rise housing have kept buildings low, and resulted

in the city favoring new construction that is traditional and suburban-looking,

even on prime residential real estate downtown.

Although a few skyscrapers have made their vertical marks,

aside from low-income housing at Barton Towers Massachusetts Avenue

and Lugar Towers on Alabama Street ,

high-rise residential development has been noticeably absent from the “city of

homes” since the construction of Riley

Center Riley Towers

The Riley

Center Indianapolis ’s

redevelopment, and of its insular business world that kept funding local rather

than federal.

Riley Center how now passed the 50-year minimum age to be

considered for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. It just might deserve a spot there.

This article appeared originally in 2007 in Urban Times. It was revised with current dates for this post.

This article appeared originally in 2007 in Urban Times. It was revised with current dates for this post.

No comments:

Post a Comment